Welcome to Paradise: The delayed arrival of the millennial dream

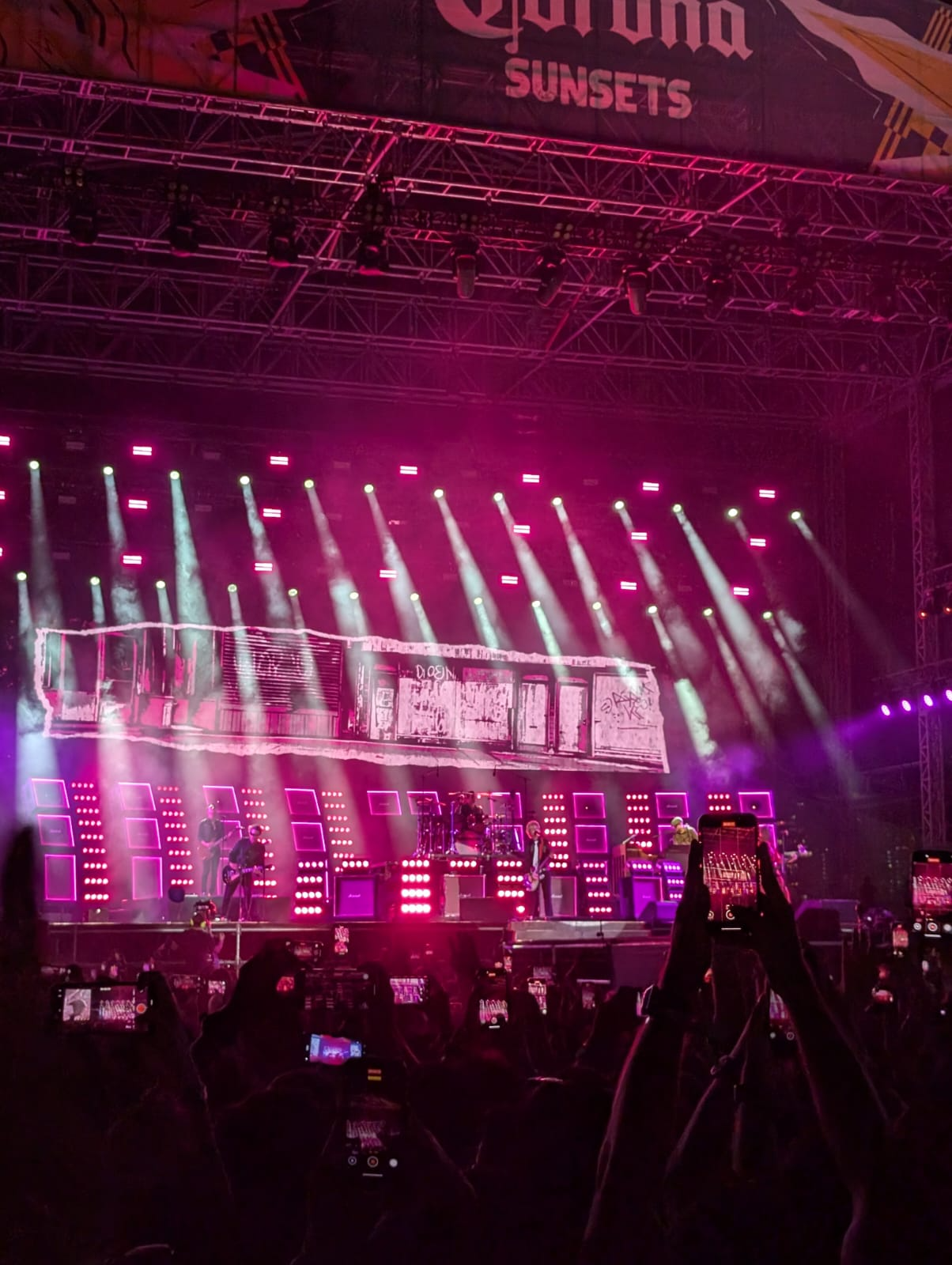

Green Day at Lollapalooza 2025

Elite urban India has measured its coming of age in the post-liberalisation era by the closeness of its consumption to the West. ‘Superpower 2020’, once a rallying cry advocating for India's rise to global relevance (now a meme), proposed a simple equation before the turn of the millennium: ‘consume like the West, become the West’. The millennials in college and entering the workforce at the time embraced this wholeheartedly, using their rising disposable income on Western imports in malls, multiplexes and music.

Of these many musical imports, American punk band Green Day captured the essence of this cohort who were ready to stake their claim over the world around them. 25 years after the turn of the millennium and five years after India's ’Superpower 2020’ deadline, Green Day has finally validated that millennial worldview. Lollapalooza 2025 was a celebration of a generation and a band that stands for something in an increasingly meaningless world.

The millennial dream has had a tumultuous journey to fruition, with its many cracks and shortcomings revealing themselves along the way. That is, until Green Day proved a long-awaited milestone in a decades-long search for closure. With Linkin Park headlining Lollapalooza 2026, it is clear that this will be a protracted millennial celebration.

Green Day on stage at Lollapalooza 2025, at the Mahalaxmi Racecourse in Mumbai

One step closer: millennials’ gradual route to finding themselves

In the 2000s, urban India (unequally) grew in opportunity. Business schools were built to teach corporate-speak for the MNCs opening offices in India. Marketing and advertising firms emerged to sell to a rapidly growing consumer class. Tech-parks cropped up to build and service the back-end of overseas clients. This generation of unprecedented affluence differed from previous generations, not just in its earning potential but also in its Westernised consumption. Dial-up internet, multiplexes and cable TV provided a window into lives half a world away, foreign lives that were aspirational but now easier than ever to recreate thanks to consumption. This consumption was material — visiting Cafe Coffee Day and Barista, or buying a Premier League football jersey — and cultural, through media.

While Western media was more accessible than before, it was still scarce: dial-up internet was unimaginably slow and expensive (compared to our post-Jio world), imported CDs were tightly regulated and costly. This scarcity forced intentionality: every download, every rip, and every CD burn was sacrosanct —precious collections built layer by layer.

The disparate but intentional process of acquiring and sharing music made communities necessary. These communities— precursors to subcultures— created a communal process to build these collections. Music was co-owned, shared through decentralised, informal networks of friends, classmates and bandmates.

Much like their music collections, millennials' identities were built gradually, with intentionality, enabled by access. None of them were born into a fully Westernised India — they watched it unfold in front of their eyes— piece by piece, with tangible, momentous shifts parallel to their lives. The first McDonald's in Mumbai opened while they were in school, the first mall opened while they were in college, and by the time they had finished their MBA, Porcupine Tree and Metallica were playing in India. It was all happening — and they could make it happen.

Unlike the buffet-style route to identity formation of the generation that followed them, or the heavily restricted, survival mindset of the time before theirs, the millennials’ identity formation was flexible and deep. It kept up with a rapidly changing world, and different ‘levels’ of identity were unlocked as technology shifted and means of access improved.

This desire to stake their claim on an evolving world, seemingly for the better, was visible in the music scene. It offered a microcosm of millennial optimism, a DIY ethos and a misplaced feeling of ‘suburban rebellion’. In an earlier article, I wrote:

“The scene was driven by a spirit of subversion— a sort of siege mentality coupled with an optimism that collective action leads to some change…The enemies were clear—Bollywood and its cousins’ chokehold on the entertainment industry, rent-seeking cops, a paucity of venues and audiences who only wanted covers of their favourite American/British bands.” – Arnav Sheth, Abandoning Authenticity, After EOD, January 2025

This was a generation that believed their music culture could change something. But soon, the dream would need a bigger stage.

Rhythm House, Mumbai— In Bombay, music shops like Rhythm House and Planet M were core memories for millennials, offering a genuine ‘third place’ where young people could just hang around and listen to CD’s. These were places music subcultures were incubated through intentionality and care. (Credits: DNA India)

Somewhere I belong: NH7 Weekender, the Happiest Music Festival

Born out of the band scene in Mumbai, NH7 Weekender best exemplified the urban Indian elite's desire to consume as the rest of the world does. Weekender was created as India's “Happiest Music Festival”, modelled around Glastonbury. Weekender was unprecedented as a format — multiple stages, multi-genre, with global artists. An outdoor festival, drenched in fairy lights and related kitsch, helped reinforce its ‘global music festival’ aesthetic.

For much of the 2010s, this ambition was realised. Weekender retained the edginess and punk-ness of the band scene, creating something of a cult following in its early days. Its platform benefited both artists and audiences. Bands breaking through around the country got a chance to play on a massive stage, and audiences were exposed to new genres and artists— thus kicking off the Weekender flywheel of discovery and adventure.

Ox7gen live at Weekender Pune 2014, with the stage decorated in phrases advocating discovery, adventure and hope

Discovering an artist at Weekender was not just plausible— it was an expectation, or even an inevitability. It stood apart from other EDM-focused festivals such as Sunburn and Supersonic. At Weekender, each stage felt like a considered, intentional extension of different parts of the millennial identity— from college-hostel icons (Karnivool, Steven Wilson, Periphery) to early-adulthood emoting (Prateek Kuhad, Parekh and Singh, When Chai Met Toast) to Indian dance music for when you were drunk enough (Nucleya, Ritviz).

While its stronghold of college students and music-scene-adjacent professionals remained loyal patrons, Weekender was reliant on its novelty as an experience, not on its lineup, to attract new audiences. This was not uncommon for music festivals — especially in the 2010s, when the ‘market size’ for multi-genre music festivals was uncertain and risky. Booking a headliner with mass appeal was a tall ask.

Working with this constraint, Weekender's programming was strategic and effective. Aware of the strength of the metal community and their depth, a not-so-famous yet still cult band like the Dillinger Escape Plan would be enough for their captive audience of metalheads to buy a ticket. A Hindi-pop act like Amit Trivedi made Weekender more palatable for first-timers. Between these were a host of fantastic ‘festival’ acts’ — not the ones you make the trip for but those you discover and take home with you. In 2014-17, The F16s exemplified the ‘festival act’— they played an early evening slot for a scattered audience— some lying on the grass, some moshing, some just walking in. It is unlikely that they pushed significant ticket sales alone, but they were an act that audiences enjoyed, many for the first time.

Weekender recognised the importance of the college student market, incentivising them to attend through their Under-21 discount, advertised by their army of campus ambassadors. This meant that Weekender, in a lot of cases, was your first ‘college trip’ — drunk off Smirnoff and a lack of supervision. Weekender’s cult-like following is evidenced by the ubiquity of those iconic steel mugs which have now been repurposed into vases, ashtrays and other showpieces across apartments in Khar, Indiranagar and Gurgaon. ‘#iwasthere’ was a core phrase that held Weekender together, visible across the festival’s stages, merchandise, and social media. It captured the essence of Weekender’s position within the zeitgeist of the mid-2010s. By being at the festival, you were not just in the audience; you were part of a larger cultural moment. You were there.

Our walk to Weekender in 2017 from our “hotel” 800 meters away, with Bisleri bottles filled with vanilla vodka

Semi-charmed life: Weekender’s plateau-ing

The millennial desire for exploration was fulfilled at Weekender. As the generation who apparently had the world at their feet, they took full advantage of the adventure that Weekender offered. But Weekender peaked in its hipster moment. It was limited by scale, and their international programming was never strong enough to put ‘India on the map’ and allow a mass-scale realisation of the millennial Indian dream.

Towards the late 2010s, Weekender’s sheen had eroded, with other multi-genre festivals to compete with (most notably Vh1 Supersonic, who leaned into their staple of large-name EDM headliners, but also added big-ticket non EDM acts like alt-j, Incubus and Bonobo). Weekender had also set expectations too high. Their loyal audience of metalheads had grown accustomed to Steven Wilson or Megadeth, and demanded stronger follow-ups as the years went by. The original #iwasthere community were making their voices heard, frustrated by the (lack of) big headliners within the larger rock/metal ambit, and the repetitiveness of the rest of the lineup. Their frustration was immortalised by the hilarious #atleasttool hashtag, which was rabidly commented on Weekender’s social media— from fans expecting an appearance from ‘at least’ Tool, the legendary American prog-metal band. Anurag Tagat wrote in Rolling Stone in 2022 –

“...we’re hoping it builds up to a bigger international metal act who can lead the way. Even if it doesn’t, Bacardi NH7 Weekender’s lineup still walks a tightrope between legacy and dependable names. It’s a letdown in some ways but certainly not in all ways, as the Internet may have you believe.”

Arriving somewhere but not here: millennials’ half-kept promises and half-baked legacy

Disappointing lineups set aside, Weekender’s proposition of a ‘Weekender State of Mind' is quintessentially millennial and unimpressive to a newer generation of festival-goers. The shared ethos of the millennial band scene— filled with discovery, community and pride in being homegrown—is rejected.

While exciting and fervent, the millennial band scene was ultimately defined by a kind of ‘suburban rebellion’ — an upper-middle-class venting with little to no political impact. This rebellion was less about transformation and more about carving out a space for ‘their’ music — detached from any intent to shift the class, caste, or gender hierarchies of the scene. Ultimately, a scene born out of a siege mentality against the powers that be replicated the same exploitative structures that they claimed to fight.

Companies like OML and Homegrown, positioning themselves as bastions of the millennial-yuppie creative industry, promised inclusivity and impact to the young professionals entering their ranks. In reality, they continued to be apolitical, vapid and exploitative. Their liberal posturing masked the truth: their prominence was built on the exploitation of women in deeply unsafe work environments, not only by individuals but also a larger system that enabled them. This broader system of creative work — then and perhaps still today — disproportionately rewarded powerful men at the helm and came at the cost of women’s careers and safety. While the financial impact of OML and Homegrown’s crooked workplaces is hard to quantify, the fallout revealed a deeper moral failure of the millennial thesis: an inability to drive meaningful change, either within their organisations or among their audiences.

From November 2018 — the headline of the Caravan’s piece on OML’s deeply unsafe and exploitative workplace. Full article can be found here.

Otherside: Finally, validation from the West

By the late 2010s, the millennial dream had faltered and the pandemic was a reset. With a break from live music and a new generation entering the workforce, a different format of music festival sprang up to cater to post-pandemic revenge partying. Music festivals were not nearly as much about adventure or exploration as Weekender’s State of Mind— instead, they now prioritise hedonism and nostalgia.

DGTL and countless dance music IPs and festivals provide avenues for hedonism, but it is only with Lollapalooza that the multi-genre festival has found its feet. Finally, ‘India is on the map’, as the biggest global music festival franchise (Lollapalooza) has recognised what the millennials have been trying to make happen for years — India as a global music market.

Through its first two editions, Lollapalooza inched closer towards the full realisation of the millennial dream. The Strokes (who played at Lollapalooza in 2023) are a millennial band, but like the Weekender trope, were a few notches off mass appeal: Manhattan-bred private school boys somehow never spoke to upwardly mobile urban India. Imagine Dragons (also at Lollapalooza 2023) had mass appeal, but given their more recent rise to prominence, their audience skew was younger than the millennial cohort. The second edition (in 2024) came closer to this delicate balance between mass appeal and being companions to the millennials’ journey, perhaps closest through OneRepublic and Keane

Was this it? The Strokes brought closure to a section of millennials, but not at scale

What’s my age again: post-dated closure in 100 minutes

If others before had come close, Green Day — who played a 100-minute set on Day Two of Lollapalooza India's third edition— was the realisation of the millennial dream. Finally, a band that they saw themselves in, one that soundtracked each formative phase in their lives Green Day was the first English band they had seen on Vh1, American Idiot was the first album they had torrented, and Time of Your Life was the song they had heard on loop after failed college romances.

Green Day’s shift from DIY punk outsiders to so-called ‘sellouts’ offers a neat parallel with the millennials’ story— who are themselves a once hungry, rabid generation that settled into quieter, domesticated lives. Yet to dismiss Green Day as mere sellouts is reductive: even today, we still see slivers of their politics. At Lollapalooza, their lyric switch in American Idiot—“I’m not part of a MAGA agenda”—alongside references to Palestine, was far more overtly political than anything attempted by Indian acts. Even if these gestures felt detached from any real world, they were still leaps ahead of their Lollapalooza peers, and certainly ahead of their stadium-concert contemporaries like Coldplay and Maroon 5. This brief politicisation may only amount to a small achievement—the kind of self-congratulation for which millennials are mocked. Yet, when set against the vacuousness of adjacent generations, it makes their attempts laudable.

The outpouring of Green Day-focused love during Lollapalooza may have appeared like nostalgia, reminiscing for simpler times in college or young adulthood, but it was not. It was closure. It was the closing of a chapter that had begun decades earlier on Limewire and at Planet M, forced onto you by an older sibling or through shared earphones in a college stairwell. Finally, ‘their’ band was live, in the flesh, in their backyard. Old black t-shirts were dusted off, hidden tattoos and scars were made visible again, and mascara (inevitably soaked in tears) was worn for the first time. For the millennials, who had the arrogance and gumption to both have dreams and try and make them come true, Green Day was an ideological and emotional companion. Decades after the black t-shirts and bootlegs have been traded for spreadsheets and speakeasies, this was a long overdue welcome to paradise.